Wyalucing

Ironies of Her Cast and Her Caste

By Lad Moore

As a courting teenager in Marshall Texas, I admittedly had more earthly items to attend to than to contemplate Ms. Inez Hughes’ meanderings concerning Marshall’s “Seven Hills” and the crumbling old plantation house she called “Wyalucing.” Although neither of the topics were subjects of any of her formal classroom lessons, this powerful teacher stirred enough interest to cause me to pause and wonder when I sometimes passed by the structure—a wonder slowly tainted as the years carved away more of its life.

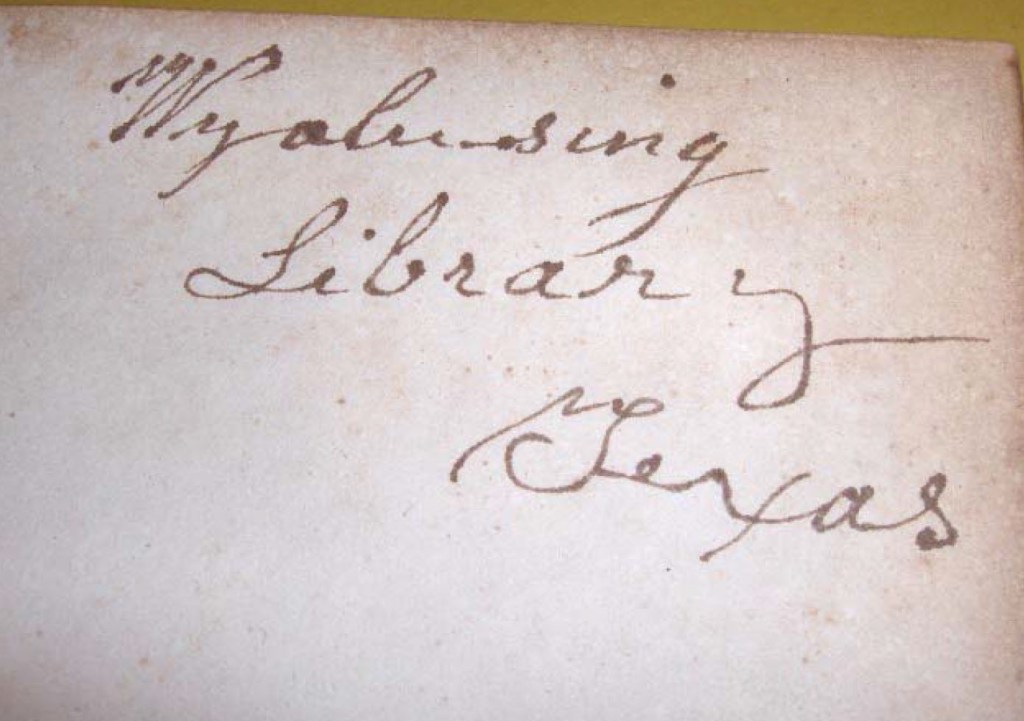

This summer, at an estate sale, my wife purchased a chafed and soiled hardback volume of Coleridge and Keats’ poetry, a first edition dating to1850. On the inside cover, in that classic flowing-hand script of the time, is an inscription that reads “Wyalusing Library Texas.” (Wyalucing is sometimes spelled Wyalusing.) I am far from a historian, and I am often given to fiction; but the book’s inscription stirred me to do a bit of digging.

~~~~

Not often elaborated upon in historical reflections of our city and heritage, for a time there stood a magnificent plantation home and associated buildings atop one of those Seven Hills of Marshall. Having stiffly soldiered columns on all four sides, the once

grand structure stood in full command of its surrounds—those regimented groves of tall magnolias that today are not even stumps. All evidence of what stood there is gone now, a casualty of bulldozers growling out the excuses we call progress. Wyalucing’s demise

came in the early 1960’s after local historians and otherwise-responsible city leaders passed on her preservation. Perhaps funding, perhaps other pressures were at work, but the reasons for that sin can never be made clear to me.

Milady’s queenly body now interred, her statuesque form and oft-lusted fragrance can now be summoned up in but lame imagination. —Lords

~~~~

We know that the brick Georgian-style plantation home, a second smaller house, and rows of slave cabins were built ca.1850 on a 100-acre tract at the terminus of today’s West Burleson Street. It was constructed by the owned slaves of Beverly Lafayette Holcombe, who migrated to the area from Tennessee. The name Wyalucing is said to be an Indian word for “Home of the Friendless.” In its early time in Marshall, Wyalucing hosted many antebellum social gatherings of the wealthy and prominent. A daughter of the family, Lucy Holcombe (1832-1899), is credited with having introduced iced tea and silk stockings to the area. She was said to be a most striking beauty, a true Southern

Belle. It was a time when the Belle title was often heard in the same sentence when addressing a plantation master as Colonel.

In 1858 Lucy Holcombe agreed to marry a Congressman from South Carolina named F.W. Pickens, a man she had been introduced to while at White Sulphur Springs, Virginia in 1856. He was twenty-seven years her senior, and courted her relentlessly despite her avowed lack of interest in him. Pickens wrote her, “Forgive me, forgive me it. I tremble for I love you madly, wildly, blindly …” Then, in a sudden reversal, she accepted his proposal. Some say it was an opportunistic reaction, contingent upon his acceptance of a foreign diplomatic post offered by President James Buchanan. A lavish wedding ceremony was held at Wyalucing on April 25 of that year. The town’s leading citizens entertained the couple the following evening with a reception at the Adkins House, the largest place in Marshall.

There is good reason to believe that Pickens wanted to do everything he could to please his Lucy, so he accepted the post and was officially named as Ambassador to Russia. (He had refused earlier offers of ambassadorships to France and England.) After lengthy travel stays in London and Paris, the couple and two of their favorite slaves arrived in Russia. Under the watchful eye of her husband she attracted much attention from Czar Alexander II, thirty-eight and restless, and whose passion for his wife was fading. He was good-natured, charming, and attractive, but also a bit timid and sensitive. His interest in Lucy assured her the entire court’s attention. He singled her out for dances, called her to stand above the ballroom on the platform reserved for the royal family and insisted they converse in French. The young Mrs. Pickens so charmed the czar that she was soon moved into the Winter Palace at the Romanoff Court. Lucy’s child was born in 1859 at the Imperial Palace in St. Petersburg and given the Russian nickname “Douschka,” meaning “Little Darling,” The Tsar and Tsaritsa became the girl’s godparents. Whispers even hint that her daughter was the czar’s child.

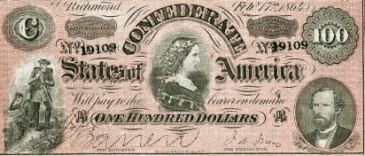

Fearing a troubled future for slavery, the Pickens family returned to South Carolina in 1860. Three days before formal secession, the legislature appointed Pickens as the Confederate Governor of South Carolina. Lucy was the perfect first-lady—a declared supporter of slavery and secession. She was known as the Queen of the Confederacy and was the only woman to have her portrait on CSA currency, adorning the One and One Hundred Confederate bills, as well as the Thousand-Dollar CSA Loan Certificate.

During the war Wyalucing played an official role in the CSA, serving as the Trans Mississippi Confederate Post Office. It was also the site of an important meeting of top CSA generals. With the surrender of Lee at Appomattox, the CSA dominos fell unit-by unit moving east to west. The more reluctant commanders of the Texas & Louisiana fields all assembled at the Plantation for a meeting to decide how best to also surrender. These men, all under the command of General Edmund ‘Kirby’ Smith, included Generals Buckner, Walker, Hawthorne and their staffs, as well as the more upstart General J.O. Shelby of “Iron Cavalry Brigade” fame. Shelby’s command had celebrated many successes in the Arkansas-Missouri theater skirmishes and in particular the 1500-mile, 42-day Missouri assault. In that campaign, over one thousand of the enemy were slain, seven garrisons captured, and over $2 million of enemy supplies destroyed. He was given the rank of General in 1863 at only age thirty-two.

At the Wyalucing meeting the group performed something of a coup d’état. They forced General Smith to resign and placed General Buckner in command, with a plan to assemble their forces in the interior of Texas and carry on the war until they were all defeated in battle.

This plan immediately fell apart. General Buckner was quickly captured and surrendered his troops in Louisiana before he could even assume the new command. General Smith then surrendered on board a ship in Galveston harbor. Smith’s last order was to send a courier to General J.O. Shelby informing him to lay down his arms and surrender his Iron Brigade immediately to the nearest union force. The furious Shelby instead rallied his men and offered them an alternative to surrender. From the balcony of Wyalucing, in an impassioned speech to his assembled command, he said, “Boys, the war is over and you can go home. I for one will not. Across the Rio Grande lies Mexico. Who will follow me there?” With this plea he won over most of the men present. Known famously as the Shelby Expedition, the men marched with shoulder arms and cannons to Eagle Pass, with prominent persons joining them along the way. While crossing the Rio Grande at Piedras Negras, they sank their Confederate guidon in the river, in what came to be known as the “Grave of the Confederacy Incident.”

Once in Mexico, Shelby offered his followers and fighting services to the French installed Emperor Maximilian. Although grateful, his offer was turned away and the group was allowed to remain in Mexico as immigrant settlers. His men now disbanded, Shelby himself occupied the hacienda of Santa Anna and began business as a freight contractor. He moved to Tuxpan in the fall of 1866, left Mexico the next year, and returned to Missouri, where he died in 1897 at the age of sixty-seven.

At Wyalucing in 1881, there occurred an event of remarkable irony. The plantation home, originally built entirely with slave labor, was purchased by some of the same and other former slaves of Harrison County. The home was to be the anchor for Bishop College, an institution slated to include a high school and college to serve black Baptists. It was founded by the Baptist Home Mission Society, the inspiration of one Nathan Bishop. Construction of additional buildings and development of the campus soon began, and Wyalucing became the residence of the first president of the new school.

The home later served as Bishop’s Administration Building, and by 1940 Wyalucing had been renamed the C.H. Maxon Music Hall. Some necessary renovation was done to the second floor to provide for piano practice classrooms. It remained the centerpiece for Bishop College until that school relocated to Dallas in 1961. Subsequent to that move, All the Bishop buildings were demolished. Majestic Wyalucing fell as well, and the grounds became home to a low-cost housing development.

Lucy Holcombe Pickens kept a diary. There is one entry where she remarks about the death of a friend. Perhaps the line is also fitting had she written it to disdain the demolition of her former home. It reads,

“Hard, indeed, must have been the heart that could have looked unmoved on the still deathbeauty of the form.”

The original Lucy Holcombe-Pickens /Wyalucing historical marker was moved from the former plantation site to the north side of the First Presbyterian Church of Marshall, where it stands today. The site is notable in that the Holcombe family, residing in the Capitol Hotel while the plantation home was being built, founded that church, and Beverly Holcombe became its first elder. Lucy Holcombe was received into the membership of the church in 1853.

~~~~

Admittedly, my treatment is briefly sketched and is a bit untidy. I have yet to find a single set of documents that unite to tell the story of Wyalucing, its cast, and its caste. So consider this article a teaser. I am sure that my good friend Ben Grant as well as others have much more that could be added to a legitimate summary—a summary that deserves a place among the other keystones that form the over-arch of Marshall and Harrison County’s celebrated history.

Fiat Lux “Let There Be Light” – Bishop College’s Motto ~~~~

Citations and Credits:

Photo of Wyalucing Plantation home cited as Public Domain

Texas State Historical Association

TAMU Commerce Digital Collections

Bishop College; Historically Black College, By Theodore Bolton Abbrev: Queen of the Confederacy: The Innocent Deceits of Lucy Holcombe Pickens Titus County Texas History: Guide to Confederate Currency

The State of Texas Online Publications

“Lost Plantations of the South” Marc Matrana

C.C. Bulger Treatise, 1936 (Attested)

“The Last Confederate General,” Christopher Egar

“Serving History, Lucy Pickens”

Handbook of Texas Online

“First Lady of the South Carolina Confederacy” Emily L. Bull

Latin-American Studies: Lucy Holcombe Pickens

Rootsweb ancestry.com

Afrotexan.com

Rendition of Wyalucing book inscription contributed by the author, Lad Moore “Lords” is a pseudonym of the author, Lad Moore

November 11, 2010